An exhibition at Chatham Historic Dockyard in 2017 explored the great naval catastrophe (from the English point of view) or audacious triumph (from that of the Dutch) in June 1667, which ended the second Anglo-Dutch War. The Dutch fleet under admiral Michiel de Ruyter sailed up the Thames and into the Medway, where the English fleet was laid up for lack of cash. They broke through the defensive chain and burned numerous ships, reserving the final humiliation for the English flagship Royal Charles which they towed back home with them. This view of the action by Willem Schellinks (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), was not in the show, but there was an impressive array of exhibits from both sides of the North Sea.

When the Dutch scrapped the Royal Charles six years later, they kept the grand ornamental stern carving of the royal arms. It now belongs to the Rijksmuseum, where along with the painting above it was part of their own celebrations of the event. However, it did apparently make a flying return visit to Chatham for the launch of the commemorations there.

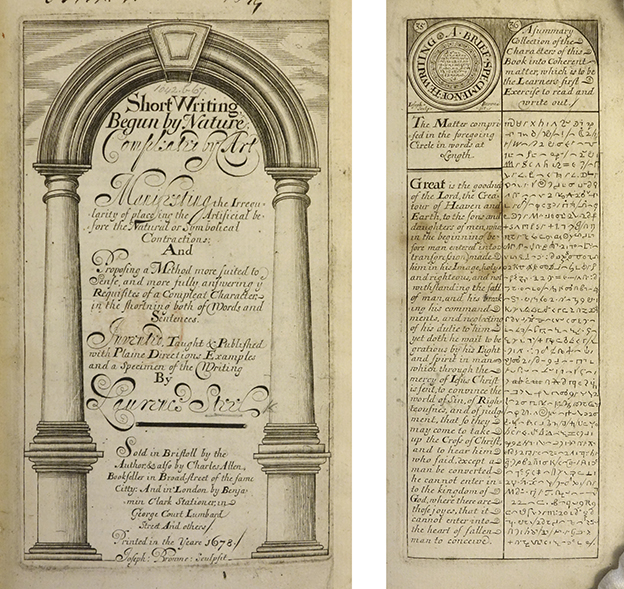

I wrote about the Medway raid earlier (here), wondering exactly how they broke the chain, and the Chatham show didn’t quite answer that but it did include a giant iron link from just such a chain. And funnily enough, a small item lent by the British Library happened to pick up the subject of another post a couple of days before this one, on shorthand (here). It’s a notebook kept by Stephen Monteage (1623–1687), whose main claim to fame is as an accountancy expert. In remarks dated ‘about June 12 1667’ on the Medway raid he includes a passage in shorthand. I don’t have an illustration, and as far as I know it has not been deciphered, so I have no idea if he had something improper to say about it or was just saving space.