Right: titlepage of The Mariners Mirrour 1588 [Folger Shakespeare Library]

The titlepage on the left belongs to a sea-atlas by a Dutch former pilot, Lucas Jansz. Waghenaer of Enkhuizen, Spieghel der Zeevaerdt, published in 1584. It was the first of its kind. The Mariners Mirrour, on the right, was published in London four years later. It is an English edition of the Spieghel, and is often described as unauthorised.

The whiff of piracy seems apt. The English edition was commissioned by Elizabeth’s chancellor Christopher Hatton, a backer of the brutal and rapacious Francis Drake, records of whose voyages have been said to resemble ‘a serial log of state-licensed maritime larceny’.[1] The stately, grave Dutch mariners on the titlepage of the Spieghel, dressed for northern waters and surrounded by instruments of their profession, have become strutting adventurers in bolstered breeches; the figure on the left with trimmed beard and full ruff distinctly resembles contemporary portraits of Drake.

![Left: detail from titlepage of The Mariners Mirrour (facsimile edition) Right: Sir Francis Drake by Nicholas Hilliard, 1581 [National Portrait Gallery]](https://thingsturnedup.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/drake_portraits_ttu2.jpg)

Right: Sir Francis Drake by Nicholas Hilliard, 1581 [National Portrait Gallery]

Waghenaer’s innovation was a volume which collated large-scale charts on a uniform scale with related sailing directions presented in a consistent format. The mainly Italian portolan charts then in use were not much bothered with north European seas; Waghenaer put into his book his own practical knowledge and experience as a pilot along with that of other Dutch navigators, whose range was rapidly expanding with the commercial growth of the northern Netherlands. The charts were engraved by Jan van Deutecum and the work printed in a grand folio volume by Christophe Plantin of Antwerp at his newly-opened Leiden printing-office, all at Waghenaer’s expense. The intermediary would have been his friend and patron Frans Maelson, an Enkhuizen diplomat and physician, but it was Waghenaer who acquired the privilege or patent for the book.

Maelson brought a copy of the Spieghel to England in 1585, when he was a member of the United Provinces delegation to Elizabeth’s court. Apparently it was much admired but an irritating language problem was noted: it was in Dutch. Late the following year Waghenaer brought out a Latin edition, Speculum Nauticum, using the same copper plates and with a dedication to Queen Elizabeth of England. In a preface he reported that the idea of producing an edition in a universal language had come from the Privy Council; he may have been persuaded by Maelson the classical scholar that this would be a smart move. However, soon afterwards Hatton ordered an English translation from Anthony Ashley, and a privilege to print ‘the Seafaring lookinge glasse’ was taken out in April 1587 by Henry Hasselup or Haslop, a London publisher and bookseller who later that year was to edit and publish Drake’s report of his raid on Cadiz. Haslop appears to have placed the printing of the atlas with John Charlewood, a man who did good business printing popular works and was not much bothered by who held the licence for them; he paid the fines and took the profit.[2] That may mean less than it implies: Waghenaer’s 1580 ten-year privilege for the Spieghel protected him only from counterfeits printed in Holland and Zeeland or imported there. In addition, he would receive one-third of any fines imposed for infringement. In 1588 The Mariners Mirrour was published in Ashley’s translation from the Latin, with charts newly engraved by De Bry, Hondius and others which closely reflected the original engravings.

It is possible that Drake, educated mainly at sea, saw the Latin-text edition; he would have been unimpressed. The lingua franca of diplomats might be Latin but for mariners it was mathematics; and the topographical description in sailing directions required the vernacular. The scholar Maelson on the other hand was a leading member of the United Provinces delegation come to ask for Elizabeth’s protection from the Spanish; he had been an envoy from North Holland to England for a decade and apparently pleased the queen – ‘Doctor Francis, whom her Majesty used with great favour in England.’[3] The Spieghel and its Latin version can be seen as instruments of diplomacy, but that remark by an English official in Holland came in 1587, by which time the resulting Anglo-Dutch treaty was collapsing and Maelson was apparently embittered (although the writer of the following bit of mud-slinging was an informant to one of Elizabeth’s spies and certainly had his own agenda):

I have heard that Dr. France, a deputy to the States of Holland from those of Enchuysen (pretty well known for his extraordinary and rude behaviour) has held very extravagant discourse in good company ; viz : that his Excellency [the Earl of Leicester] had very greatly wasted the substance of the country ; while said country was very happy that the time of his government had expired … That the Queen was a virtuous princess, who would do very great good to the country if only she would be pleased to send her treasure hither, instead of her English, who could be very well done without.[4]

Clearly, The Mariners Mirrour is not so much homage to Waghenaer’s creation as wholesale plagiarism – a term that had not quite arrived in English then (although the original Latin coinage to mean literary kidnapping goes back to Martial in the 1st century). But the book breached no patent, and Waghenaer himself appears to have had no wish to risk his money on an English edition. The Spieghel was reprinted four times in two years and, thanks to Maelson, the States of Holland and West Friesland granted him a substantial sum in recognition of its importance, which relieved his perennial cash problem (he had a large family). Plantin would have taken the sales revenue. Before Waghenaer’s privilege for the Spieghel expired he transferred it to the Amsterdam publisher Cornelis Claesz. There is no record of what the deal was worth, but Claesz. went on to produce numerous editions in several languages. Waghenaer’s concern was that although Claesz. had bought the privilege for the book alone, if he were to renew it he would try also to get his hands on Waghenaer’s separate patent for two large portolan charts of Europe; he had heard that Claesz. was already working on one of them.[5] The sale of loose charts must have been where Waghenhaer saw his financial security, the bread-and-butter work that freed him to develop his project: an authoritative book of navigation and seamanship.

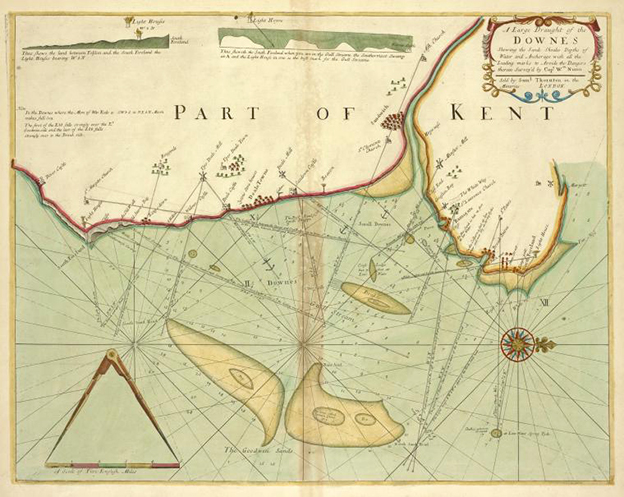

The Spieghel was magnificent, and it had paid the bills, but it was not what Waghenaer originally set out to make. It was a collector’s volume: a finely-printed folio, beyond the means of the fellow-mariners for whom he intended his work. Its success did however bring him the resources to try again, with a new sea-pilot in a more portable format: the Thresoor der Zeevaerdt had a wider geographical range, and the navigational data and sailing directions were expanded and updated. (In it he returns to the confusing business of the Downs at Deal discussed in a previous post, with a label ‘Duns’ on the land instead of in the sea below as Ashley had it, and a reference in the sailing directions to ‘de derde witte crijt-berg’ – the third white chalk-peak.)

The Thresoor was also printed at the Plantin shop in Leiden. The first chart, of the coasts from Holland to Flanders, Waghenaer dedicates to Maelson, ‘Amplissimo Clarissimoque Viro D. Doct. Francisco Petro Maelsonio Enchusiano … in perpetuae obseruantiae mnemosynum’; he identifies himself as its originator, and perhaps vendor: ‘Auctor Lucas Ioannes Aurigarius [helmsman] 1590’. Evidently it was intended to be sold separately as well as appearing in the book. The map-maker Abraham Ortelius (recipient of an advance copy of Waghenaer’s Spieghel from Plantin) explained the economics of book publishing to his cousin, who had asked for advice about a book of his own:

As far as my experience goes authors have seldom obtained money for their books, as these are mostly presented to the printers, but they usually receive a few printed copies, and generally expect also to get something for their dedication, according to the liberality of their patron, which often or mostly (I believe) fails them. I was present when Plantin received a hundred ‘daelders’ into the bargain from Ad. Occo. for printing his work on medals, probably because the printer thought that the book would not sell very well. So also in the cases of books which are very expensive on account of many engravings, the author has to defray the cost.[6]

Ortelius’ view is that authors write ‘for the sake of honour, or to acquire friends, or to receive remuneration from their patron, or to earn a reputation (for which reason many fools write books nowadays)’.[6]

In 1601, the year his patron Maelson died, Waghenaer was granted a government pension, but on his own death five years later his widow was left without means; Waghenaer had accumulated no wealth from his life’s work. And yet: it is his name, not Maelson’s or Skelton’s, that lives on and is honoured. Sea-pilots were known among English speakers as waggoners until the eighteenth century, and in 1985 the pioneer of charted depth soundings had a sea-bed formation named after him. The Waghenaer fracture zone is located about halfway between the Bering Strait and Australia.

Notes

- Mark Netzloff, ‘Sir Francis Drake’s Ghost: piracy, cultural memory, and spectral nationhood’, in Pirates? The Politics of Plunder, 1550–1650, 2007, p. 140.

- R A Skelton, Bibliographical Note, The Mariners Mirrour, facsimile edn 1966, p. VIII; Oxford DNB, 2004.

- 15 October 1587, Richard Lloyd to Walsingham, ‘Elizabeth: October 1587, 11–20’, Calendar of State Papers Foreign, Elizabeth, vol. 21, part 3: April–December 1587 (1929).

- 8/18 March 1587, Ringault to Wilkes, ‘Elizabeth: March 1587, 1–10’, Calendar of State Papers Foreign, Elizabeth, Volume 21, Part 2: June 1586–March 1587 (1927).

- 5 Letter Waghenaer to Maelson, in C. Koeman, The history of Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer and his ‘Spieghel der Zeevaerdt’, Lausanne, 1964, pp. 28–29.

- Letter Ortelius to Emanuel Demetrius, 17 November 1586, J H Hessels ed., Epistulae Ortellianae, 1887, no. 148, pp. 341–42.

Further reference

- In London, the British Library has first (i.e. Waghenaer’s) editions of Spieghel der Zeevaerdt, Speculum Nauticum and Thresoor der Zeevaerdt; the British Library and the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, each have a copy of The Mariners Mirrour.

- C Koeman, The history of Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer and his ‘Spieghel der zeevaerdt’, Lausanne, 1964

- R A Skelton, ed., Spieghel der Zeevaerdt, facsimile of the first edition 1584–5, Lausanne, 1964

- R A Skelton, ed., Thresoor der Zeevaerdt, facsimile of the first edition 1592, Lausanne, 1965

- R A Skelton, ed., The Mariners Mirrour, facsimile of the English edition 1588, Lausanne, 1966

![Frans Maelson by Johannes Wierix, 1572 [British Museum]](https://thingsturnedup.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/maelson_small.jpg)