This exuberant creature is seakale, very much at home in St Mary’s Secret Garden in urban Hackney. Crambe maritima is a member of the cabbage family; it has a Caucasian cousin cultivated for its flowers, which look like a white explosion. This Crambe, however, is a thing of shingle and salt winds, at home in Derek Jarman’s wild garden on Dungeness.

Nicholas Culpeper of Spitalfields described the seakale plant in The English Physitian Enlarged of 1653, along with information on its habits and its curative virtues:

They grow in many places upon the Sea Coasts, as wel on the Kentish, as Essex shores; as at Lidd in Kent, Colechester in Essex, and divers other places, and in other countries of this land … The Broth, or first Decoction of the Sea-Colewort, doth by the sharp, nitrous, and bitter qualities therin, open the Belly, and purge the body; it clenseth and digesteth more powerfully than the other kind. The Seed hereof bruised and drunk, killeth Worms. The Leavs or the Juyce of them applied to Sores or Ulcers clenseth and healeth them, and dissolveth Swellings, and taketh away Inflammations.

Seakale has been cultivated since at least the eighteenth century. Phillip Miller, gardener to the Apothecaries’ Society at their physick garden in Chelsea, gave advice on the cultivation of Sea-Cabbage in his Gardeners Dictionary (1731). He noted: ‘it is found wild upon the Sea Shores in divers Parts of England, but particularly in Sussex in great Plenty, where the Inhabitants gather it in the Spring to eat, preferring it to any other of the Cabbage Kind’.

The plant had its keenest advocate in a self-taught botanist named William Curtis. As a boy in the 1750s he roamed the fields and meadows around Alton in Hampshire with a knowledgeable friend. Alton was a thriving place of watercress beds, paper mills and breweries, and the Curtises were a substantial local Quaker family, many of them apothecaries or surgeons (young William’s father was a tanner, his grandfather a surgeon-apothecary). The naturalist Gilbert White’s parish of Selborne lay a few miles away.

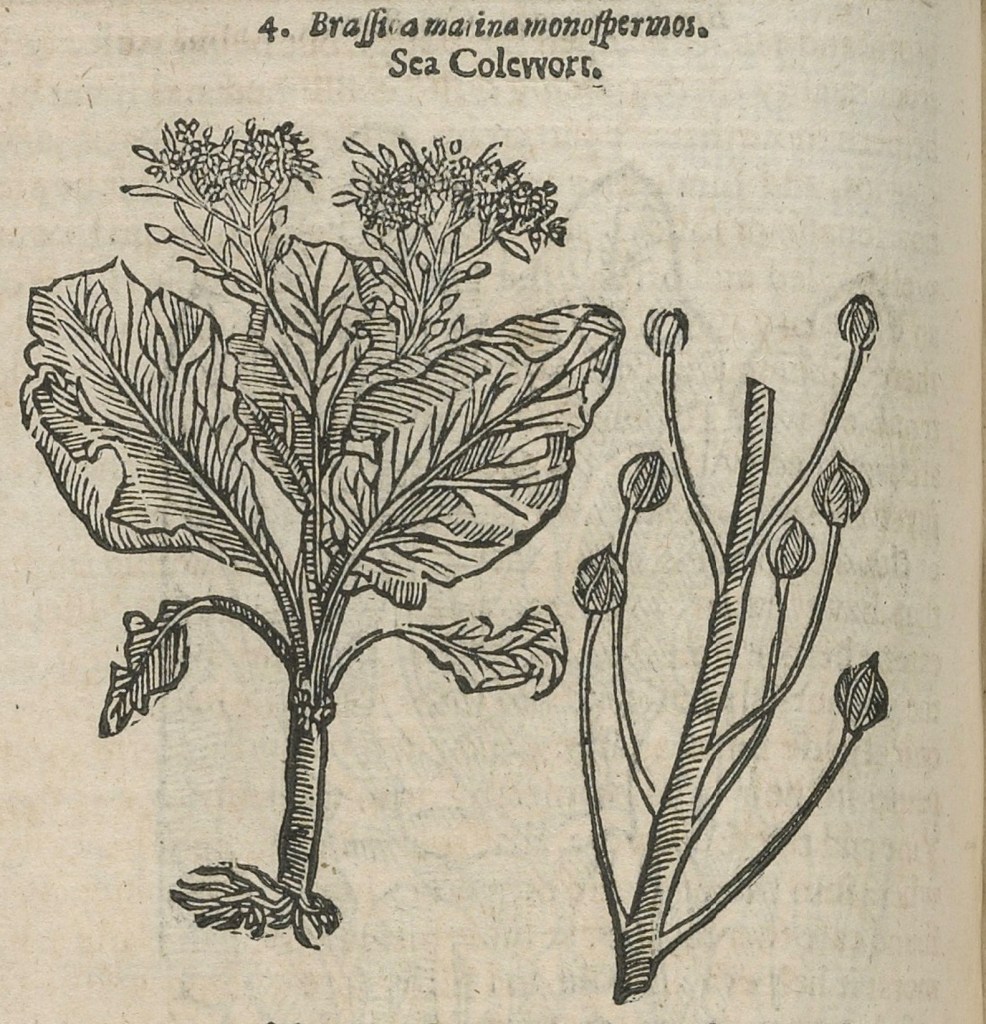

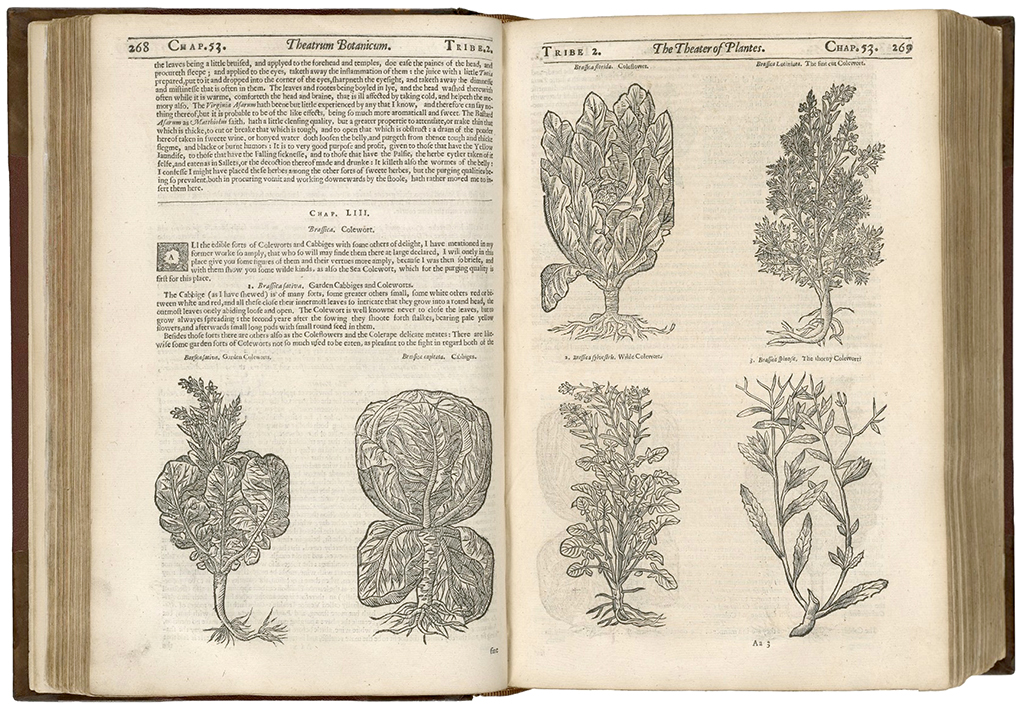

William Curtis’s friend William Legg, who looked after the horses at the inn next door, had educated himself with the aid of Gerard’s and Parkinson’s herbals from a century earlier. John Gerard’s The herball, or, Generall historie of plantes (1633) had a woodcut of seakale and a brief description translated from a Dutch herbal. John Parkinson in his Theatrum Botanicum (1640) was more forthcoming. He called it Sea Colewort, described it, and noted that it grew wild on the Essex coast, at Lydd in Kent and at Colchester. In his arrangement of remedies it was classed as a purgative, like the rest of the colewort or cabbage family. Nicholas Culpeper judged Parkinson’s herbal a hundred times better than Gerard’s and depended on it for his own herbal.

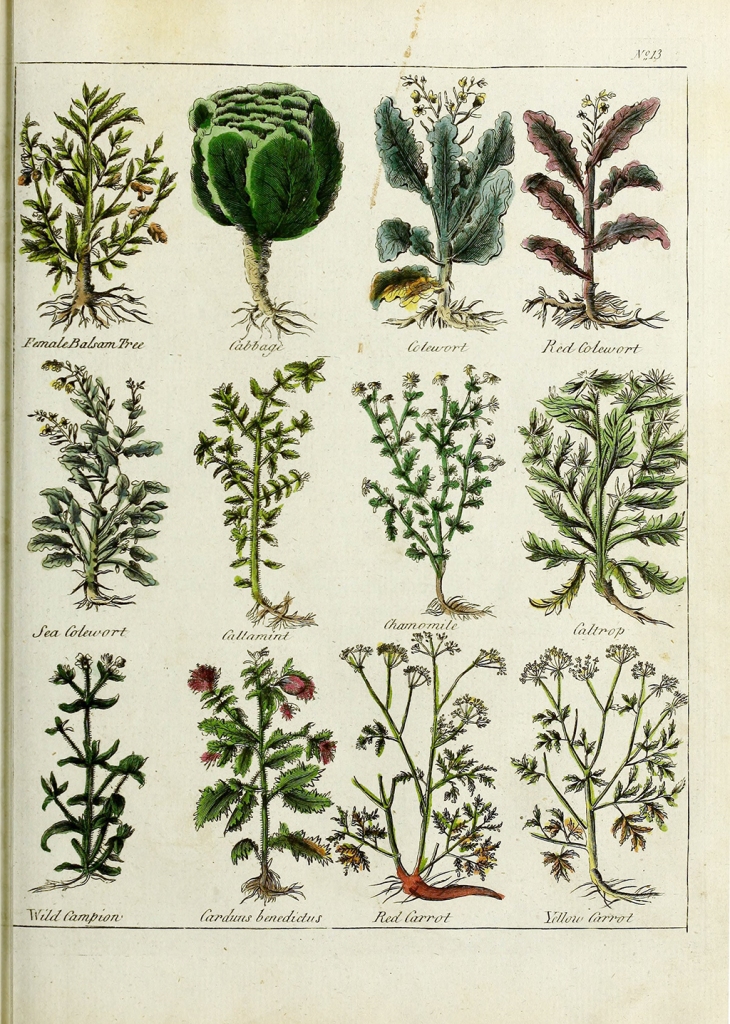

Woodcut book illustrations could be printed on the same page as the text (and for the purchaser willing to pay extra, also hand coloured). Culpeper’s The English Physitian Enlarged of 1653 had no illustrations, and he died soon after it was published. But the book has lived on through the centuries in numerous editions. The first illustrated edition came in 1789, published by the entrepreneurial Ebenezer Sibly as Culpeper’s English physician; and complete herbal, ‘beautified and enriched with engravings of upwards of four hundred and fifty different plants’. As engravings on copper plates they were printed separately and then bound in with the text.

How Sibly acquired the plates for Culpeper’s Complete Herbal is unclear. If they had once carried the signature of their engraver it was now erased. They add up to a tremendous body of work done by skilled but nameless engravers, letterers and colourists, copying from multiple sources. The difficulties are evident. On this cabbagey page the letterer has muddled up two of the labels. Seakale appears in the top row, but is labelled Colewort. The wild cabbage (Brassica oleracea), is illustrated in row two, and happens to be a direct copy of Parkinson’s woodcut of ‘Brassica sylvestris, Wilde Colewort’ (see previous image), but here it is wrongly labelled Sea Colewort. And yet this colourist has recognised the seakale plant, from nature or from Culpeper’s description (also borrowed from Parkinson) – ‘this hath divers somewhat long, broad, large, thick, wrinkled leaves, crumpled upon the edges … very brittle, of a greyish green colour’ – and has painted it accordingly. In a different copy of the book, another colourist has painted the seakale a lettuce-like green.

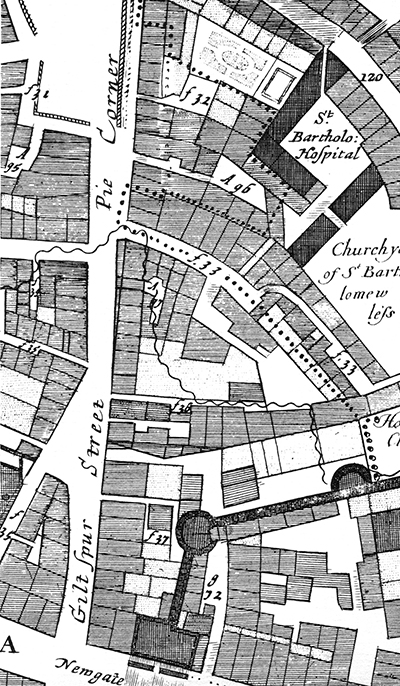

William Curtis, who had begun his education with the old herbals, knew the problem. Through apprenticeship he qualified as a member of the Society of Apothecaries and succeeded to his master’s London practice, but his true love was botany. ‘The street-walking duties of a city practitioner but ill accorded with the wild excursions of a naturalist; the apothecary was soon swallowed up in the botanist, and the shop exchanged for a garden’, wrote a fellow-naturalist. Curtis became an acknowledged plant expert. During his employment as demonstrator of plants at the Chelsea Physic Garden he translated Linnaeus’s Fundamenta entomologiae, and argued strongly for the general use of scientific classification. Later he would establish his own botanical gardens for the cultivation of native British plants.

Gilbert White of Selborne’s younger brother Benjamin was a prosperous London bookseller and publisher whose shop at the top of Fleet Street was a meeting place for naturalists. He and Curtis were friendly, and together they occupied a small garden in Grange Road, Bermondsey, in which to cultivate British plants (I suspect that White paid the rent while Curtis did the gardening). It was with Ben White’s assistance that Curtis embarked in 1775 on the publication of Flora Londinensis, a heroic attempt to survey every plant that grew wild within ten miles of London. It was a finely-illustrated folio series in which the plants were engraved life size. Each 12-page number was priced at five shillings coloured, 2s 6d plain, or 7s 6d if coloured with extra care; but this ambitious project threw Curtis into debt and it was never completed.

It was in Grange Road that Curtis had chanced on his first illustrator, a young immigrant from Dublin who happened to be living there. William Kilburn’s engraved plant portraits for the Flora Londinensis have, I think, a distinctive kind of wayward grace and vitality. But to support himself, his widowed mother and his sister he needed a more dependable income than Curtis could provide, and he was succeeded as engraver by James Sowerby and Sydenham Edwards. For his designs for printing on calico Kilburn is now better known than Curtis. (I am at present researching the lives of William Kilburn and his variegated relatives, so this post represents a bit of work in progress.)

Seakale makes no appearance in the Flora Londinensis, but Curtis knew the plant well. When he laid out his botanical garden at Brompton he set aside seven acres ‘for experiments in agriculture’, where he cultivated seakale. Later he devoted an entire tract to it, entitled Directions for cultivating the Crambe maritima, or sea kale, for the use of the table, in which the plant is illustrated. On the particular copy shown here, the page is marked by an offset of the library stamp of one of his patrons, Joseph Banks.

Here is William Curtis on seakale:

Its full-grown leaves are large, equalling in size, when the plant grows luxuriantly, those of the largest cabbage, of a glaucous or sea-green hue, and waved at the edges, thick and succulent in their wild state … On many parts of the sea-coast, especially of Devonshire, Dorsetshire, and Sussex, the inhabitants, for time immemorial, have been in the practice of procuring it for their tables, preferring it to all other greens; they seek for the plant in the spring where it grows spontaneously, and as soon as it appears above ground, they remove the pebbles or sand with which it is usually covered, to the depth of several inches, and cut off the young and tender stalks … In Devonshire particularly, almost every gentleman has a plantation of it for the use of his table; we have been informed that it has for many years been cultivated for sale in the neighbourhood of Bath; and my friend, Mr Wm. Jones of Chelsea, tells me that he saw bundles of it in a cultivated state exposed for sale in Chichester market, in the year 1753 … Many conceiving that stones, or gravel, and sea-sand, are essential to its growth, are at the expence of providing it with such, not aware that it will grow much more luxuriantly on a rich sandy loam, where the roots can penetrate to a great depth.

Curtis remarks that seakale when young ‘is to be served up to table on a toast with melted butter, in the manner of Asparagus’. If you wish to grown your own seakale, William Curtis can tell you all you need to know. Directions for cultivating the Crambe maritima, or sea kale, for the use of the table, was published in 1799, the year of his death. You can find it online.