Tace was almost unknown as a given name in London before the Quaker printer Andrew Sowle and his wife named their fourth daughter in 1666. It was a little less rare elsewhere; it crops up from the 1540s in the earliest Church of England registers, notably in Gloucestershire and the west. Andrew’s mother was baptised Tace in the small village of Winstone, near Cirencester, in 1603, and his sister also bore the name. His father Francis moved the family to Smithfield on the edge of the city of London in the 1640s, and it was in London that Andrew raised his own family. After that, the name proliferated throughout their extended clan.

Tace is from the Latin meaning ‘be silent’, and the rural parishes where it appeared were mostly in parts of the country where religious dissent flourished. William Camden knew it: in Remaines of a Greater Worke Concerning Britain (1605) he lists it as a Christian name for women, with the comment: ‘Be silent, a fitte name to admonish that sex of silence’. It has an air about it of a Puritan name, but as an emblem of anti-episcopal belief it is in the wrong language. In English, as Silence, it occurs from early in the seventeenth century, mainly in Yorkshire.

An older potential source for the name is Gesta Romanorum, a medieval compendium of tales and fragments which was mined for plots by numerous writers, and for parables by sermonising clerics. The story there of the Three Cocks contains the rhyme ‘Audi vide tace si vis vivere pace’ (hear, see and be silent, if you want to live in peace): a suitable motto for dissenters hoping to keep a low profile, you might think, although the name itself would tend to have the opposite effect. Printed Latin editions of Gesta Romanorum first appeared in the 1470s; Chaucer knew the story a century before that and used it in the Manciple’s Tale. Needless to say, it was almost exclusively girls who had this obligation to silence conferred on them by baptism, although audi vide tace was later taken up as a motto by English freemasons.

In parish registers you can sometimes catch the sound of names from three or four centuries ago, when a clerk has spelled an unfamiliar name as it was spoken to him; this one was pronounced Tacey. Others would have recognised its source and known the meaning. The Quakers were viewed with curiosity and usually derision for their practice of having women preachers, and in the late 1600s there was a genre of satirical prints which showed a woman standing on a tub to speak at a Quaker meeting. An inscription under one of these, in the decade when Tace Sowle took over her father’s press, includes what may be a direct reference to her:

Flusht with Conceit (which she the Spirit calls)

Upon a Tub see how Dame Silence bawls

Whilst Dunghill Cocks in a most pious strain

Listen to heare the Cackling of the Hen

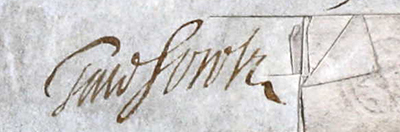

As it happens Tace was not a preacher, but she published other women who were, and as a resourceful printer and bookseller she had considerable heft. There are no portraits, but her signature suggests fluent self-confidence. The print below depicts a generic repellent–ridiculous preacher-woman; though less of a caricature than some (no dog cocking its leg on her skirt), it cannot be a likeness.

![The Quakers Meeting by Marcel Lauron after Egbert van Heemskerk, 1690s [Library of the Society of Friends]](https://thingsturnedup.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/heemskerk_meeting.jpg)

The tone of the attack on Dame Silence is a startling reminder of the fearful misogyny paraded by 21st-century internet trolls – which would make Tace Sowle a forerunner of Mary Beard, Caroline Criado-Perez, Lindy West and a great many other women who make themselves heard now. There is more about her as a printer in this post.