That depends on who’s being asked, and possibly on who’s doing the asking. On the south-west Donegal coast of Ireland in the 1970s, a neighbour advised me that the then-current British Admiralty charts should not be trusted, at least where names were concerned. The charts were derived from an 1859 hydrographic survey, the first of that stretch of coast, and were originally engraved in 1860–61. Apart from compass variations they had not been noticeably updated since then. It was still recalled locally with some satisfaction that the navy men had toured the area asking inhabitants what names were in use there, and duly recorded a series of obliging but mostly spurious answers.

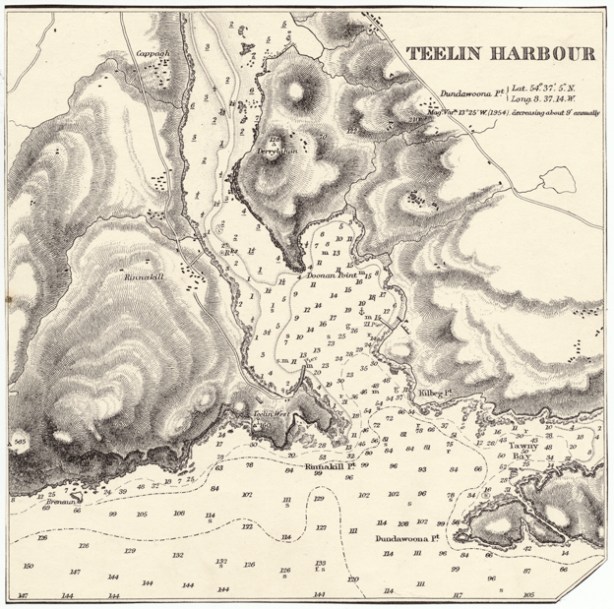

Somewhat disappointingly, the names on the charts of the coast around Teelin, in the civil parish of Glencolumbkille, look very much the same as the ones I heard there in the 1970s. And the army had been there already. Seventeen years before Commander G A Bedford of the British navy arrived in 1852, the Ordnance Survey was in Donegal, on a government project to map all the townlands of Ireland for taxation purposes. The survey was directed by Colonel Thomas Colby of the Royal Engineers and the work driven by a heroic data-mapper, Lieutenant Thomas Larcom. It employed civilians to research local pronunciation of Irish place-names and establish Anglicised spellings. Chief among these was a celebrated Irish scholar and topographer, John O’Donovan, who as a young man spent seven years touring Ireland on toponymic fieldwork, often travelling on foot (and little legs – he was 5ft 2in tall). The place-names around Teelin on a 1967 revision of the sea charts mostly echo those on the Ordnance Survey six-inches-to-the-mile map of 1836, although the charts add some names of coastal features. One at least of these looks a little suspect, among the transliterations: a rock below Slieve League labelled with the frankly English words Giants Rump. An Irish speaker familiar with that coastline might have more to say about it. And if the navy borrowed from the army, the latter probably reciprocated. In his history of the Irish Ordnance Survey, J H Andrews quotes one of Larcom’s successors writing accusingly of the method used to put low-water mark on the Donegal maps: ‘I suspect it to have been obtained from an Admiralty chart’. Andrews adds: ‘the Survey was never very happy about taking to the water’.

O’Donovan saw his work on names as a project of Irish scholarship; but the wide-ranging commentaries he sent back to Dublin remained there in manuscript, and it is unlikely that Bedford saw them. O’Donovan did, however, encounter some local difficulties which have a familiar ring. From Dunfanaghy in the north of the county he reports that for the names of coastal features – rocks, holes, clefts, heads and points – he consults fishermen; a few days later he adds ‘I am sick to death’s door of the names on the coast, because the name I get from one is denied to be correct by another of equal intelligence and authority.’

O’Donovan was an Irish speaker, but he was from Kilkenny and his Irish would have been that of an easterner, very different from Ulster Irish. The latter, according to native Donegal speakers in the 1970s, had enough in common with Scots Gaelic that Irish and Scottish trawlermen were able to keep in touch with each other over the radio and pass on information about where the herring were without alerting English fishing fleets. O’Donovan underlines his own cultural separation from his informants when he observes of the parish of Glencolumbkille: ‘Social immobility seems to me the dominant trait in the character of these people, who live in what may be called the extreme brink of the world, far from the civilization of cities and the lectures of the philosopher.’ And on top of that, he was the army’s man. People in Donegal may have felt scarcely more reason to trust him than they would the British military and the government, or to recognise any common purpose.

Cartographic politics thrown into focus by the 1830s Ordnance Survey have been the subject of Brian Friel’s play Translations, and of a continuing debate arising from it. The Ordnance Survey of Ireland was run from Mountjoy House in Dublin and the six-inch maps of Ireland were engraved there. Following the partition of the country the Irish provisional government insisted on the return to them of the copper printing plates and other materials relating to the Irish survey, which had been progressively removed to the Ordnance Survey’s headquarters in Southampton; in 1923 these were allocated between the Free State government and that of Northern Ireland. On the other hand, if there was a maritime commonwealth of north-western Celts, yet the new Irish state did not get sovereignty over its waters until 1938. And the British navy still rules the mapping of the Irish waves – for now, at least. In the online world there are people working on the idea of crowdsourced hydrography.

By the time the finely detailed and vigorously engraved Admiralty charts of Donegal came to be published, production had already been outsourced, to the London firm of J & C Walker, prolific map and chart engravers. Relief on the charts is visualised by means of hachures whose lines follow the fall of the slope. Range upon range of dark, knobbly mountains give the charts an energetic beauty absent from the Ordnance Survey’s six-inch maps, which were initially hill-free but during the 1840s and 50s acquired the cool precision of contour lines. Contours matter if you want to lay a railway, for example; mariners need to know how the land looks. In fact the Admiralty charts do show contour lines where they are wanted: they connect soundings of equal depth and so describe the sea-bed. Both sets of vertical data proceed from sea-level; how best to establish a datum point in a moving body of water caused the Survey much difficulty. It is necessarily a fluid concept.

As for George Bedford (not to be confused, as he has been in an official history, with his brother Edward, also navy hydrographer and at that time surveying the complicated west coast of Scotland): his orders, like O’Donovan’s, were to use the acknowledged local names. Did he have the wool pulled over his eyes? I don’t know, but the story has a kind of truth to it anyway. Writing about another part of the Celtic world, Rowan Williams (late of Canterbury) refers in a recent review to ‘a time-honoured Welsh tradition of poker-faced amusement at the expense of the conquerors’.

Mexican postscript

A peninsula in central America is said to have got its present name when newly-arrived conquistadors asked the people they encountered there what they called it. The locals replied in their language that they could not understand the Spaniards’ speech, and the latter duly rendered what they heard as Yucatán. But the source of this story, sometimes attributed to Cortés, remains slippery; it has the air of being one more seductive frontier myth.

Sources

- John O’Donovan, Ordnance Survey letters Donegal : letters containing information relative to the antiquities of the county of Donegal collected during the progress of the Ordnance Survey in 1835, Michael Herity ed., Dublin 2000

- J H Andrews, A paper landscape: the Ordnance Survey in nineteenth-century Ireland, 2nd edn, Dublin 2001

- Sir Archibald Day, The Admiralty Hydrographic Service 1795-1919, HMSO, London 1967

- Rowan Williams, review of RS Thomas: Serial Obsessive by M Wynn Thomas, The Guardian, 6 April 2013 http://gu.com/p/3ept5

- Images of the six-inch plans are online at Ordnance Survey Ireland http://maps.osi.ie/publicviewer/ (listed as Historic 6”)