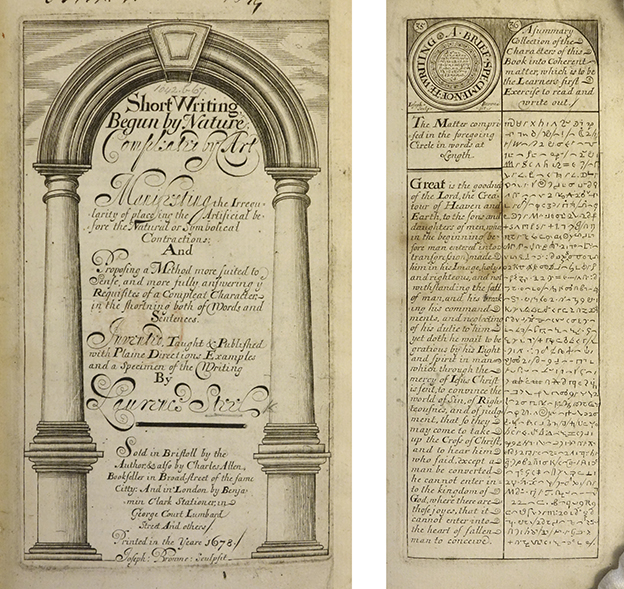

This detail is from the title page of a teach-yourself shorthand manual entitled Short Writing, Begun by Nature, Compleated by Art, written by a Bristol Quaker schoolmaster named Laurence Steel and published in 1678. It was not the first – stenography handbooks promoting various systems were published throughout the 1600s (and shorthand was already in use centuries earlier, in Ancient Greece and then in China, according to Wikipedia).

But early Quakers had particular reason to want a means to record speech verbatim. They were repeatedly arrested and brought to trial under laws designed to suppress religious dissent; they argued their cases tirelessly in court, and evidently produced verbatim records of proceedings against them, since some of these were published. I don’t know if any such shorthand manuscripts have survived, either by Quakers or from the thriving commercial publication of state treason trials. The best-known contemporary user of shorthand was Samuel Pepys, for his own reasons.

Steel’s handbook with its gloopy script is printed entirely from engraved plates using a rolling press, rather than from movable type on a common press – the ordinary wooden press used then for printing books – and its unnamed printer was not Andrew Sowle, the Friends’ own printer. The latter did however have extensive personal experience of harrassment and prosecution by government, and his daughters and apprentices were themselves resistant to constraint in various ways. Andrew Sowle endured repeated imprisonment, break-up of his press and types and seizure of his stock for seditious printing. His daughter Tace succeeded him and ran the press for half a century. His first apprentice fled to Amsterdam after printing the rebel Duke of Monmouth’s manifesto, and may also have been William of Orange’s printer in Exeter; his eldest daughter married another Sowle apprentice and with him became notorious for press piracy; another daughter married a third apprentice and emigrated with him to set up the first press in Philadelphia, where they fell out with a new Quaker establishment.

Some time back I started writing a blogpost about this clan of unstoppable printers, but the word-count shot up to something unfeasible almost at once. So now it’s a book, called Dissenting printers, and has its own page in the menu bar.

![The Quakers Meeting by Marcel Lauron after Egbert van Heemskerk, 1690s [Library of the Society of Friends]](https://thingsturnedup.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/heemskerk_meeting.jpg)